1864 – 1937

Karl Williams continues the exploration of the great figures in history in his Geoists in History segment.

“There never was a time when the need was greater than it is today for the application of the philosophy and principles of Henry George to the economic and political conditions which are scourging the whole world. The root cause of the world’s economic distress is surely obvious to every man who has eyes to see and a brain to understand. So long as land is a monopoly, and men are denied free access to it to apply their labor to its uses, poverty and unemployment will exist. Permanent peace can only be established when men and nations have realized that natural resource should be a common heritage, and used for the good of all mankind.”

“I am of the opinion that (economic) rent belongs to society and that no single person has the right to appropriate and enjoy what belongs to society.”

“Until they had abolished landlordism root and branch, every other attempt at reform was building upon the sands. Every reform not based on common ownership of the land was simply subsidising landlordism. Every social reform increased the economic rent of land. Therefore, unless they were going to continue to waste their efforts by tinkering with social questions as in the past, they must concentrate upon this fundamental question, to secure the land for the people.”

“Users of land should not be allowed to acquire rights of indefinite duration for single payments. For efficiency, for adequate revenue and for justice, every user of land should be required to make an annual payment to the local government equal to the current rental value of the land that he or she prevents others from using.”

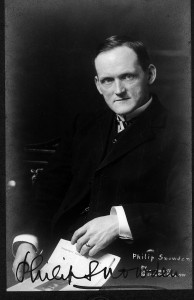

Raised in a humble Yorkshire cottage, the son of a weaver, Philip Snowden rose to be Britain’s Chancellor of the Exchequer and, if that be promotion in his eyes, a Viscount (“First Viscount Snowden”) among its ancient aristocracy. He displayed the riches of poverty when sustained by strict principles, by religious faith, and by a keen interest in social evolution. His geoist principles were instilled in his early childhood in the way that his lowly neighbourhood cottagers who, drawing their water from a well in a nearby field, had risen in physical revolt against the attempt of the landowner’s agent to make a charge for its use. Who can wonder at the bent given to a child’s mind by such an experience?

Snowden’s parents were devout followers of the religious ideas of John Wesley and he was brought up as a strict Methodist. He followed his father’s example and never drank alcohol. A clever lad, he was soon top of the village school. He passed the prescribed examination for a lower grade of the Civil Service and became a surveyor of inland revenue in the Treasury – no-one would ever have imagined that this mid-ranking public servant would twice be its Ministerial chief.

Early setbacks, rather than privilege and comfort, are often seen to more roundly shape a man’s character. In Snowden’s case, it could even be said that “if it doesn’t kill you, it’ll be good for you” as he was hopelessly crippled by an affliction of the spine which followed an accident, and he was forced to leave the Civil Service.

Snowden’s wide-ranging ideals lead him to meet and marry Ethel Annakin, a campaigner for women’s suffrage. Snowden supported his wife’s ideals and he became a noted speaker at numerous public meetings as a member of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage.

But politics was Philip’s real interest, though the turmoil surrounding British party politics at the time forced him to change party a number of times. At first he joined the Liberal Party but when researching a speech on the dangers of socialism, Snowden felt moved to instead join the Independent Labour Party. Later on he joined the Labour Party and in 1906 became their MP for Blackburn.

This was the pivotal and perhaps most impressionable period in his life, amidst the great push for geoist economic reforms led by Lloyd George and Winston Churchill whose “People’s Budget” of 1909 proposed taxation on the unearned increment in land values, to be implemented when a land valuation register was ready. Snowden wrote extensively on economics and advised Lloyd George on this budget.

During the Great War Snowden braved widespread unpopularity because of his opposition to the conflict – he never wavered from pacifist ethics and offered his support to conscientious objectors. This cost him his seat in the 1918 election but he recovered his popularity and his seat in 1922

Snowden found that, in the shifting sands of political alliances and deal-making of the time, his proposals were all subject to great compromise. When Ramsay MacDonald formed the first Labour Government in January, 1924, he appointed Snowden as his Chancellor of the Exchequer. Snowden not only had to convince the electorate of his geoist proposals, but also many of his Labour colleagues as well as Liberal coalition partners. To this end, one of his famous utterances was “We hold the position that the whole economic value of land belongs to the community and that no individual has the right to appropriate and enjoy what belongs to the community as a whole. Let there be no mistake about it. When the Labour Government does sit upon those benches it will not deserve to have a second term of office unless in the most determined manner it tries to secure social wealth for social purposes.”

Snowden reduced taxes on various commodities and popular entertainments, but was criticised by members of the Labour Party for not introducing any socialist measures. Snowden replied that this was not possible as the Labour government had to rely on the support of the Liberal Party to survive. Less than a year after becoming Chancellor, Stanley Baldwin, the leader of the Conservative Party, became Prime Minister and Snowden’s period in office came to an end.

However Snowden returned to government with Ramsay MacDonald’s victory in May 1929 and was again appointed Chancellor, but more political turmoil soon ensued. His economic philosophy was one of strict Gladstonian Liberalism rather than socialism. His official biographer wrote that “He was raised in an atmosphere which regarded borrowing as an evil and free trade as an essential ingredient of prosperity”. Snowden adopted a Land Value Tax in Labour’s May 1931 budget and his resolution read, “There shall be a tax …. of one penny in each pound of land value of every unit of land in Great Britain.” The bill involved between 10 and 12 million separate valuations. Snowden told the parliament, “We are asserting the right of the community to the ownership of land. If private individuals continue to possess a nominal claim then they must pay rent to the community privilege. The great land owners cannot be permitted to enjoy the privilege to the detriment of the welfare of the community. Land was given by the Creator, not for use of dukes, but for the equal use of all his children.”

However late in 1931 the Conservatives came to power once again and quickly stopped the land valuation and abolished the tax. Snowden’s geoist budget had caused a tremendous uproar among Conservative land owners and was considered a direct challenge to neoclassical economics and its privatisation of natural resources.

Created Viscount Snowden of Ickornshaw in 1931, Snowden then sat in the House of Lords, serving as Lord Privy Seal but resigned in 1932 when free trade was abandoned the next year. Exhausted from politics, he then had little involvement in the political world and died in 1937.

Despite the political disorder of his day, Snowden stood firm on many noble principles. Besides his unwavering pacifism, Snowden held a lifelong aversion to Toryism, jingoism and any form of privilege. In his personal life, Snowden had vanquished poverty from the outset by the simple process of reducing his own wants to principles of voluntary simplicity (in monetary terms, a very modest thirty shillings a week) and charged little for his lectures. He was able to pursue a life of broad interests and proud independence. Little wonder, then, that Churchill – who spent most of his political life on the opposite side of parliament – said of Snowden, “He was really a tender-hearted man, who would not have hurt a gnat unless his party and the Treasury told him to do so, and then only with compunction. Philip Snowden was a remarkable figure of our time“. It’s pretty hard to improve on Churchill’s summation.