EMPTY HOMES

Housing is a human right, not a privilege. The housing and land in our cities is a valuable asset.

But a significant portion of it is being withheld from productive use.

Property owners focused on capital gains face no strong incentives to put vacant housing to use, thanks to a tax system skewed against workers and renters – one that rewards unproductive asset holding while penalising productive activity.

Prosper’s Speculative Vacancy reports have drawn attention to this issue since 2007.

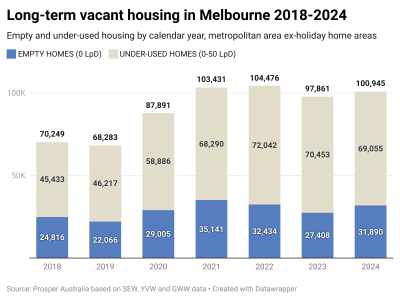

Our 2025 data update reveals a 16% increase in totally empty homes, bringing the total to 31,890. Including underused homes – using less than a quarter of the average one-person home – the figure climbs to over 100,000.

Prosper Australia’s latest Speculative Vacancies data update reveals a 16% rise – to 31,890 – in totally empty homes in Melbourne over the past year. This rise in empty dwellings has undermined the benefit from new housing supply coming online.

Including a further 69,055 underused homes, the total climbs to 100,945. This figure speaks to a significant misallocation of resources that we can’t simply build our way out of.

Melbourne’s vacant housing stock is equivalent in scale to two and a half years of new construction. We have enough vacant housing to give every single person on the Victorian public housing waitlist a home – twice over.

Rental vacancy statistics won’t tell you this. Melbourne’s empty homes are hidden from view. These missing rentals are inflating the cost of housing, making life even harder for those struggling.

Our reporting aims to bring these facts to light.

For some, leaving homes empty is a rational choice. The value of the flexibility to sell or reoccupy an untenanted house can exceed the yield from renting it out. Other homes are empty simply because the wealthy owners feel no need to use them. That renters cannot afford to outbid the convenience value of an empty property speaks of deep inequality – the root cause of unaffordable housing.

But it also illustrates how housing supply is at the mercy of speculative incentives.

It’s not just empty homes where we see speculative withholding of resources. The pace of new construction is driven by the returns to speculation too. As our 2022 Staged Releases report showed, when land banking is more profitable than development the market drip-feeds land and housing to buyers as a result.

These two speculative behaviours – land banking and vacant housing – are barriers to housing supply that Prosper wants to see better recognised in housing policy debates.

The state of Victoria has led the way with policy. Its 2017 vacancy tax was the first of its kind in Australia, and Prosper supported the 2023 announcement to expand the tax state-wide and apply it to undeveloped residential land, with stricter enforcement of non-compliance.

But vacancy taxation is a second-best solution – an improvement on the status quo, but still an administratively cumbersome and intrusive means of drawing property into use.

A more durable solution to the waste and inequity of land speculation is to shift taxation onto land using broad-based land taxes and value uplift capture.

These taxes are simple and fair. They respect property rights and incentives while treating land as it should be treated – as a shared community asset. Land is an essential for life. It should not be a financial asset monopolised by the privileged.

Properly taxing land is a core part of the tax shift we need for a prosperous, equitable future. You can read more about our Tax Shift vision here.

- Check out our latest data update

- Read the latest speculative vacancy report

- See past speculative vacancy reports

- Join the Tax Shift campaign

- Stay updated on our work by joining our mailing list

Subscribe to our newsletter

Be the first to hear about our latest research, campaigns and upcoming events.