# 2 12 December 2008

Ineffective demand: a picture of a tax-induced economic depression

In the 2nd of this most important series of commentaries warning of the looming depression, Bryan Kavanagh interprets one of his most important graphs. Mr Kavanagh lists the reasons why the GFC has occurred via an overview of recent tax trends. Essential reading.

What’s wrong with this picture?

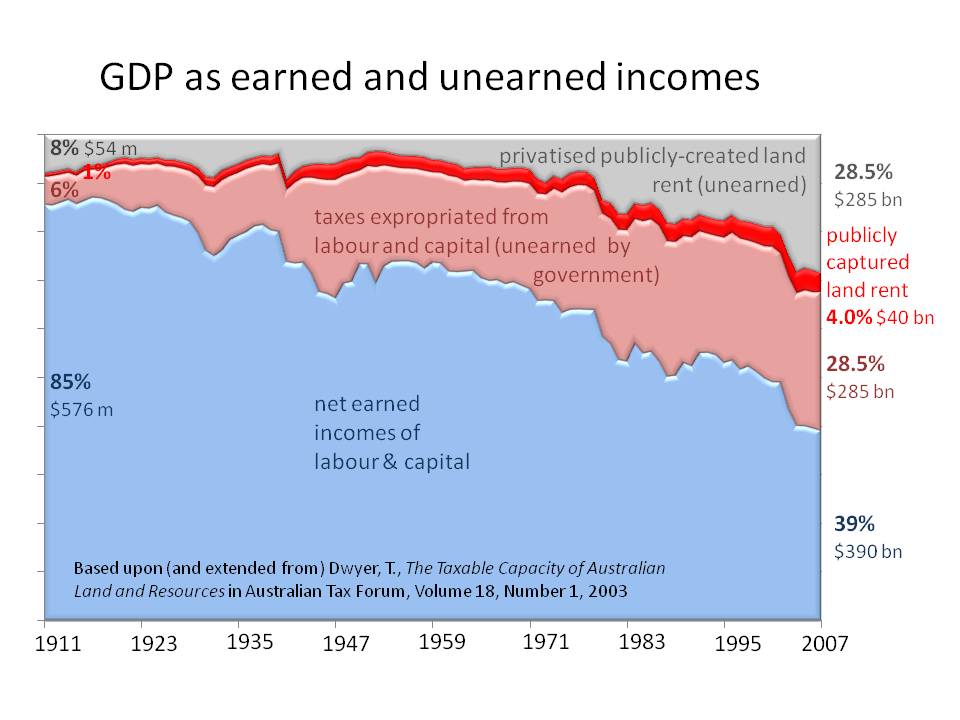

There’s nothing wrong with it – except for what it portrays. It depicts Australia’s gross domestic product descending into an economic depression because a badly-designed tax system has finally choked off effective demand – almost completely. This unique portrayal separates earned incomes from unearned incomes and closely approximates what has taken place in other economies.

Why is it ‘unique’? Because it at last assesses the extent of rent within the economy. In economic terms, rent is the annual value of a nation’s land. It’s literally a natural source for revenue, because no individuals have created it. It’s the value that the public and community infrastructure gives to the land as we work away at our jobs each year. Although it is a surplus value (because it’s community-generated, not a production cost), we capture only 12% of it to the public purse (less than $40 billion of $325 billion) in Australia. The graph shows that rent is now sufficient to replace taxation at all levels of government. i.e. If we were to collect it all, there would be no need to tax (or fine) labour and capital for working!

Although it would do away with the taxation of labour and capital were we to capture our land rent rent for necessary government, we’ve permitted landowners to retain 88% of it, even though they’ve done nothing to earn it. And, of course, those who get the greater part of our rent are those who own not only the most land, but also the most valuable land. People who rent their homes receive no rent from society at all, although their presence did help to create it (not as individuals, but as a group). So, it is unfair in the extreme that rent – being generated by everyone – is collected only by the wealthier segments of society.

Therefore, as Australia allowed rent to be privately expropriated, it became necessary to tax labour and capital more heavily for working, in order to make up the difference necessary for public finance. The effect of this has been to reduce the returns to labour and capital severely, as shown in the chart. If we were to capture more of our land rent, wages and capital would retain a greater share of their earnings and – instead of capturing only $390 billion in 2007 – these two factors of production would collect nearer to the full $675 billion to which they are entitled; that is, which they earned.

But the reduction of the earned incomes of labour and capital is only part of the story of Australia’s sharp decline into economic depression. Returning to the graph, it may be seen that net wages and interest (the net returns to labour and capital after taxation), grew only 677 times since 1911 as their proportion of GDP declined from 85% of GDP to 39%. Effective demand has been eroded slowly but surely. Taxation meanwhile grew by a factor of 7000! Herein lies another great economic truth: every bit of the increase in taxation was necessarily added into Australian producers’ costs.

There is one thing on which economists do agree – that, unlike taxes, rents cannot be passed on in prices in a competitive economy. Therefore, to claim that Australia can’t compete with China, or other ‘low wage’ countries, is a nonsense. We could become cost competitive overnight simply by cutting our counter-productive taxes and increasing our land-based revenues.

Unlike the share of labour and capital, Australia’s land rent grew by a factor of 5400 between 1911 and 2007, from $60 million to $325 billion, and because almost all of this was privatised, we get an insight into the process that enriches the wealthy at the expense of the Australian community as a whole – they leech parasitically off its rent. Nor is that the entire story. While rent has always grown strongly with the community and its infrastructure, it climbed particularly rapidly since 1980, during the period of so-called ‘economic rationalism’, as it became popular to ‘pooh pooh’ community values and to sell off the public’s assets to rent-seeking companies. Rent represents community, insofar as it is generated by the existence of the community, but we permitted the enormous increases shown in land rent to flow into a few private pockets. In so doing, the recent massive increases in rent were also capitalised into escalating land prices, impossible levels of household debt and larger and larger mortgages.

So, like most of the world, Australia grinds to a halt as both labour and capital are caught in the jaws of the rent-seekers’ vice, that is, between a declining share of GDP and higher and higher taxes and land prices. We compensated the earned incomes we lost to taxes and privatised rent by borrowing greater sums from banks – just to exist. Whereas Charles Dickens’ character, Wilkins Micawber, came to learn that this was quite an unsustainable position, the framers of our taxation policy have still not learned this lesson.

Labour has been denied effective demand by means of the private capitalisation of extraordinary levels of rent into astronomically high land prices and mortgage debt that has become impossible to repay.

Since the beginning of the 1980s, the Australian taxation system has emitted a glowing green signal to property speculation and a red light to labour and capital. The current depression is therefore an entirely logical outcome of a corrupted revenue system, and the economy has finally surrendered to the idiocy of our tax policy.

It is sometimes said that we live in a ‘computer age’ and ‘land doesn’t matter anymore’, but this ignores that everything we produce still comes from land – even the computer chip. So, we need to capture a far greater share of rent for public revenue if we are to re-establish cheaper access to land and permit labour to combine with land to generate capital and wealth again.

Despite the graph’s portrayal of an inverse relationship between the private capture of rent and the returns to labour and capital, there has been very little analytical recognition that our deepening economic woes emanate from the excessive privatisation of Australia’s land rent. Instead of the government sacrificing huge sums of money into a deflationary vortex in the forlorn hope of resuscitating the economy, Ken Henry’s review of Australia’s Future Tax System needs to give a lead by slashing labour and capital taxes to the bone and capturing much more of our rent for revenue. Real estate speculation can no longer remain a sacred cow.

Bryan Kavanagh

Land Values Research Group

Melbourne

Trackbacks/Pingbacks